ELIMINATE DOWN - MAY 2024

The Friends of Eddie Coyle/The Towers of Toron/The Fortress of Solitude/Whores for Gloria

Among Philadelphia’s best bookstores is Lot 49 Books, now located in Fishtown but previously located much closer to me in South Philly. True to its Pynchon namesake, I first learned about them via flyer. Seeking them out, I was greeted by a table of paperbacks out front of the shop. On this table was William Vollmann's Rising Up and Rising Down, his (abbreviated!) 750 page nonfiction meditation on the history of human conflict and a wealth of premium grade pulp paperbacks. This, I knew, was my spot. The sky was overcast that day, the air heavy. Rain was imminent and I knew that the one guy working inside would not be able to rescue this outdoor collection from Philadelphia's surprise downpours in time. I grabbed two books; the Vollmann and a pulp novel whose name I recognized from a movie - The Friends of Eddie Coyle. After digging in their stacks for a bit, I came out to the counter with more than I could buy. I set down the Vollmann - having a rule that no more than two unread Vollmanns should occupy a shelf at any given time - and kept Eddie Coyle.

The Friends of Eddie Coyle - George V. Higgins (1971)

Both books had clearly been rained on before. The Vollmann had it worse, a phone book thick tome that still felt soft to the touch like a pulp-paper sponge. Eddie Coyle was what I'd call appropriately weathered. It looked musty, it smelled mustier, I'm almost convinced there is mold growing on the spine where the glue meets the page. For a pulp paperback, there can be no better condition. It sat on my shelf for months. I doubted my impulse purchase, something I'd picked up on pure recognition and kept because its ultimate fate would be the trash if someone didn't take mercy. When assembling the List, I thought this would prove just okay. I enjoy my Richard Starks and Jim Thompsons but if you look at my shelf, you'll notice they're absent. Grabbing Higgins seemed like a castaway wish. Not so. I finished it in under twenty-four hours, an admittedly unprecedented mad dash of attention pored over the damn thing.

Higgins’ lean prose and tight dialogue made the task easy. There’s no flowery language here, it’s a mean machine. Higgins is locked tight on Eddie’s dilemma. The situation is more complex than Eddie thinks it is, there’s an intricate sprawl to Eddie Coyle. Aside from its titular character, the perspective shifts to the story’s other operators. The most inline with Higgins' lived experience as Assistant U.S. Attorney is Dave Foley, an ATF agent trying to flip the gun runner Coyle as an informer. Foley is a genuine demon, a wolf in coyote’s clothing. There’s also Dillon, who Peter Boyle portrays in the film, the simpering, see-no-evil bartender that serves as secret interlocutor between Foley and Coyle. There’s also Jackie Brown, a younger small-timer who Coyle knows he can set up as a patsy. The cast of characters expands out from there but just about every character intersects with another by the story’s conclusion. It’s well-plotted and the snaking of character relationships makes it a page turner in every sense of the phrase.

Higgins sets up chapters like scenes in a play. Characters occupy static recurring locales - bars, cars, grocery stores, police precincts and trailer homes. They chat, do business and exit scene. Sometimes the scene goes terribly awry. There’s a heavy emphasis on dialogue, substantial portions of the book are dedicated to men trading off lines, seemingly waiting for the screen adaptation or courtroom recitation. That this was Higgins’ first novel makes sense. It is so stripped to its bare essentials, embarrassed by hints of emotion beyond the facts and motivations that it feels properly, oppressively macho. It’s an unmistakably Irish Catholic book, one that is textually indebted to Irish Americans acting as both *the* cops and *the* robbers in New England. When Higgins worked for the cops, he didn’t just work any old beat, he was in Massachusetts’ anti-organized crime division. Eddie Coyle is about identifying snakes in the grass and Higgins turns Massachusetts into Ilha da Queimada Grande.

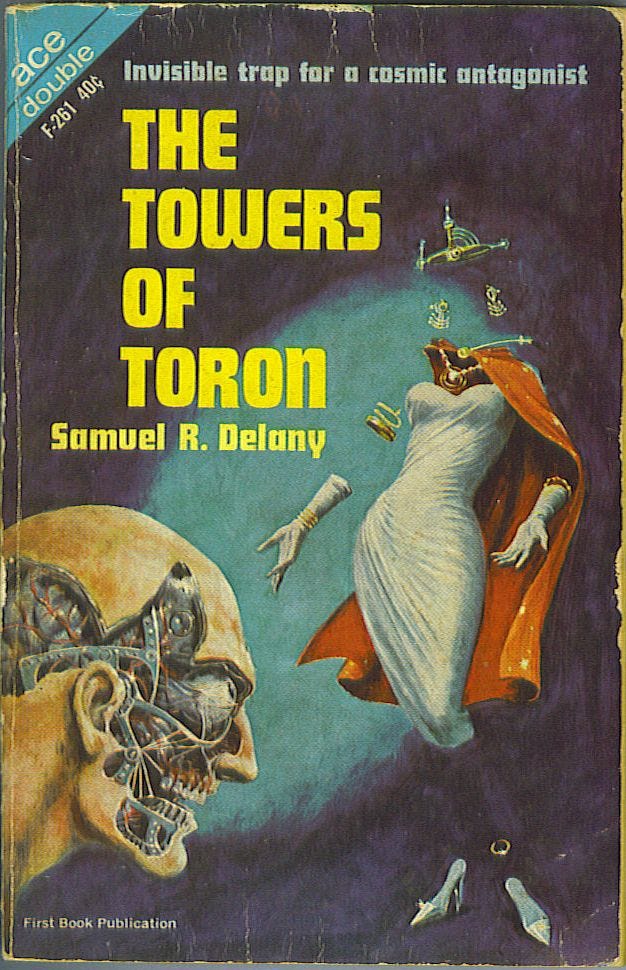

The Towers of Toron - Samuel R. Delany (1964)

Published when he was 21, The Towers of Toron was the third book that legendary science fiction author Samuel "Chip" Delany ever published - the second book in his "Fall of Towers" trilogy. Delany's an author I've wanted to track down for some time, first learning about him through a discussion on his 1999 non-fiction Times Square Red, Times Square Blue - a blend of memoir and urban design essay detailing how Manhattan cast the LGBT community out. He’s better known for his science-fiction, being one of the new-wave’s most prominent and notorious authors. His legend in the scene is that his books are explicitly philosophical, often elaborate digressions about theories of language and sexuality more than they are straightforward narratives. One of his most popular books, Babel-17, was mostly a convenient way for him to talk about linguistic relativity and get paid for it. Even his smut is heady!

Some of these hallmarks are present in The Towers of Toron but the bulk of the book feels more in line with the culturally conscious pulp science fiction that presaged the new wave movement. For as much as I'd like to be able to talk about The Towers of Toron, it didn't leave much of an impression. When I purchased it, I knew it wouldn't be the ideal entry point for the author. But I thought, “hey that's okay, I'll track down his other stuff.” And then I decided to embark upon this challenge. It was doomed to fail. Jumping blind into book two of a trilogy is a bad idea and I spent roughly seventy pages playing catch-up to the events of the last book which Delany helpfully retells in conversations interspersed throughout. What is here is well written with some suggestions of the ambition, creativity and conscience of his later books but it is buried under a lot of talk of princes and gizmos and flames and walls.

The racial hierarchy on Toromon opens the book up as both a racial and queer allegory and Delany is able to repurpose the atavistic depictions of other cultures and races found in Burroughs or van Vogt as prescient culture commentary. It escapes me if Delany has intentionally deployed this as meta-commentary on a genre he appreciates and is well-versed in. The way he renders common othering tropes like height differentials and ESP as sympathetic leads me to believe that he was actively resisting the resting current of his contemporaries’ descriptive language. The final twist of the book wherein it is revealed that the war being fought on the margins of the civilization is actually a simulation and that those fighting it are actually in pods connected to a computer superstructure beat The Matrix to the punch by at least thirty five years. It still registers with a measure of dramatic urgency and clarity of vision that made sticking by the book feel justified. This was a poor place to jump in but Delany remains a fascinating character and this isn’t the last of his works you’ll see in Eliminate Down.

The Fortress of Solitude - Jonathan Lethem (2003)

Here we go, another logjam, Jonathan Lethem's bildungsroman The Fortress of Solitude. This one entered my collection through regular collection enabler Mike Pavese and to him, and him alone, I apologize for my negativity on this one. It is important to not to make criticism of Jonathan Lethem too personal or even reflective of his talents in a strictly professional way. He is doing enough of that himself - his most recent book "Brooklyn Crime Novel" is written almost as a postmortem on Fortress. From a 2023 article in The Nation; "It was only after he was able take in The Fortress of Solitude off-Broadway musical that he reconsidered. He began to imagine people who, in fact, “fucking hate” his celebrated novel and he decided “to method act that from the inside.” What if it was like a consensus? People were like, ‘That book was horseshit.’ …‘Well, I’m not a novelist, but I’m going to fix this. And I’m going to do it by any method I can, slapping on documentation, getting other people to talk, just whatever it takes to tell the story without the Dickensian glow.’” But it's worth looking back at Fortress to understand why its "Dickensian glow" as Lethem refers to it has worn so thin so quickly.

The Fortress of Solitude is divided into three sections; the first - Underberg - details the childhood of Dylan Ebdus in the third person with Ebdus acting as author stand-in. The second section, Liner Notes, is written by Ebdus for a compilation album of another character's songs. The third section, its most chronologically ambitious, is told in the first person and jumps from present day 1999 before floating back to fill in the missing sections of the characters' lives as young adults. Lethem renders the Brooklyn of his childhood, specifically Gowanus, with incredible detail. He is able to shape it to scale with the characters' memories. When Dylan is a child, his neighborhood seems enormous, labyrinthine, dangerous. As he grows into adolescence, the rest of New York City opens to him and Gowanus begins to feel smaller, less challenging, a mastered territory. Lethem probes at the differences in life experience between his stand-in, Dylan, and his black friend - Mingus Rude. For much of the novel's first half, Lethem's exploration of the schism between the opportunities offered to Dylan versus those offered to the cooler, older, idolized Mingus draw out striking observations on how the cool white kids of NYC were often liberally borrowing from their black neighbors, often out of respect or outright admiration but nevertheless borrowing, plagiarizing. The culpability of well-meaning white people in gentrification of both culture and land is at the core of Lethem's story.

Underberg's ending lays Lethem's weaknesses as storyteller on the table and color the remainder of the book both overly stylized and self-congratulatory. Borrowing liberally from Marvin Gaye's infamous death at the hands of his father, Lethem consigns Mingus Rude to prison with Dylan bearing witness but otherwise escaping unscathed. Not two pages later, Lethem name drops Marvin Gaye in Liner Notes. I dislike these conspicuous allusions to black tragedy. I take umbrage with Lethem restitching Gaye’s death as clothing for his characters while also using Dylan to profess his guilt over using familiarity with "cool" "black" signifiers like graffiti, drugs, and music history to attain liberation from his home neighborhood. There’s a psychologically complex profile that Lethem develops here and not one I'm completely unsympathetic toward. Much of American popular culture is sourced, uncredited from black communities and Lethem is making a sincere acknowledgement of that and grappling with the idea that up to this point in his life, he's exploited this social construction. But at 522 pages, The Fortress of Solitude continues this exploitation.

Lethem writes Dylan with genuine pathos and the character is rich with internal conflict and vulnerability. When the question of the character's bisexuality is posed, it doesn't feel gawking or insincere, it feels in line with how Dylan has observed interpersonal relationships and mutual attraction. His depth has the effect of drawing out how scripted the black characters are. They don't share that same depth. They exist as tokens of culture for Dylan to grow from and apologize to. When Mingus reciprocates Dylan’s kiss, it exists in the context that he has seen his addict father perform similar acts. For Dylan it can be passion, for Mingus it can only be a reprisal of trauma. The calculation that Lethem makes is that his sincerity will register with the reader and that the pessimism that codes the close of the book, that good intentions will not absolve you, will serve as a sufficient bulwark against critiques of shallow caricature. However, the style of literary fiction that The Fortress of Solitude practices has a habit of precociousness and this habit is all over Lethem's writing.

I was first acquainted with Lethem's writing through his 33 1/3rd of Talking Heads' Fear of Music. Among the more generally reviled volumes of the series, his examination of Fear of Music spends a not insignificant amount of time evading discussion on the songs to instead diagnose David Byrne with autism. It is one of the volumes of the series where it feels like the author is more proud of their research than they have anything to say. So goes The Fortress of Solitude. The conspicuous name-dropping spikes to deafening levels when Dylan enters adulthood where he works as a music journalist. This particular frustration is one that Lethem is intentionally eliciting. What is Dylan but a collection of his influences, repurposed and reconstituted into a form resembling a man? But this point is well worn by the book’s third act and the 2000s lit-fic tradition of self-righteousness wears out its welcome with each successive page. It's well-written, occasionally dazzling, but too obvious a stab for great American novel status. After The Fortress of Solitude, Lethem would continue writing but the consensus seems to be that if the literary world will remember a 2000s Jonathan, it'll be Franzen.

Whores for Gloria - William Vollmann (1991)

Covering topics as far ranging as Japanese Noh theater, campaigns of settlement & displacement in North America, climate science, prostitution, and the history of human conflict, William Vollmann is one of the most prolific living American writers. Notorious for the length of each of his projects, the total sum of his bound-and-published writing coming in at roughly 17,589 pages, reading everything he’s written could take a person a lifetime. So here I am reading an appetizer, the 160 page Whores for Gloria, his shortest novel but one that is no less brilliant, grotesque and indicative of Vollmann's idiosyncratic style.

I first became aware of Vollman when my brother lent me his earliest short story collection, The Rainbow Stories, while I was in high school. At the time, those stories were the most difficult I'd ever read. The subject matter was often dark and distressing, the prose alternated between arcane and ultramodern, and the constant switching between the abstract and the literal was too much for my teenage brain to process. That said, it was extremely influential in my tastes and when I visited San Francisco as a teenager, I nearly dragged my sister to a reading of his at City Lights but lost my nerve not knowing what I'd be revealing about myself in doing so. Vollmann writes so candidly on society’s seedy underbelly that I blanched at the idea of someone inevitably rejecting his work or being made to feel uncomfortable by the uncompromising material.

What I found most striking about his stories was their empathy. Many of The Rainbow Stories are set in San Francisco, specifically the Tenderloin District. Not quite a Red Light district but not quite a slum, the Tenderloin is where San Francisco's addicts, drunks, homeless, sex workers, and other groups discarded by society gather. The implicit goal of the short story collection is to render its characters with a vibrancy and emotional depth that makes them seem more human than their street descriptors; "skinhead", "whore", "zombie." It's a noble cause and almost all of Vollmann’s later work, including Whores For Gloria, continues to wave the banner of his difficult, peculiar humanism.

The novella is told as a series of scattered vignettes with headings emphasizing key information; a narrator, story detail, or theme. Opening with a brief note that the man’s narrative is fictional but the stories told by the girls are sourced from real sex workers, Whores for Gloria immediately feels like a continuation of Vollmann’s Bay Area fiction. The composition of their vignettes feels as if you’re being spoken to and Vollmann relays these stories without turning the subjects into objects of pity. He creates space for the women to talk about clients, dreams, plans, their day-to-day.

What Vollmann excels at is making the abstract feel tangible. The Rainbow Stories assigned colors to emotion, inducing a synesthesia-like effect on his prose. That talent carries over here. The descriptions are vivid, often vulgar, sometimes beautiful, occasionally repellent. There are passages where he curtly describes assholes “bulging like sausage casings” but he regularly lapses into extended sequences that capture the gloss of nostalgic reverie; half-invented, half-remembered, fully intoxicating.

Whores for Gloria uses Jimmy as its askew lodestar. An alcoholic Vietnam veteran who flops around the Tenderloin using up his government paycheck on booze and cheap sex while obsessing over “Gloria”, we find him beginning to conduct physical and mental rituals to make his fantasy manifest. He asks prostitutes to tell him stories that he then weaves into the backstory of the fantasy Gloria’s life, he makes a gnarled wig out of one woman’s hair for other women to wear during sex, and he pleads with the ghost of the unfinished Gloria in his flophouse room. Meanwhile, his body decays from the effects of alcohol abuse and venereal disease, compounding his already fragile mental state. The decay is observed from all sides; we know how Jimmy sees Jimmy, we know how other Tenderloin residents see Jimmy, and we know how we see Jimmy. Some details remain elusive. There are suggestions that Gloria may have been a lover, a neighbor, a total stranger, or that these rituals might be Jimmy displacing his own femininity. Vollmann doesn’t dwell on this last hypothesis any more than he dwells on the other stories and ideas in the book. Like much else in the book, Jimmy’s memory of this is depicted with emphatic tenderness;

In the summer Gloria and her friend Shawna used to play in the rubber wading pool in the backyard and they would stay in there for hours pretending to be mermaids and calling each other mermaid names like Pearl and Crystal and Jimmy was jealous but Gloria said no you can’t be a mermaid and Jimmy said aw why not and Shawna said he can get in too I don’t care but Gloria said no he can’t because you have to be a girl to be a mermaid and anyhow we don’t have a third mermaid name to call him, so Jimmy had to run through the sprinkler and watch the rainbows in the arches of water that curved up into the air like silver ribs and they sprayed down on the newly cut grass that was so wet and made the bottoms of his feet green and Gloria laughed and said look at Jimmy running and Shawna said Jimmy can run so fast can’t he Pearl and Gloria said yes so fast Crystal and Jimmy was a still a little cross but Gloria said I want you to be a boy not a girl and anyway I like you best of all.

As I mentioned at the start of the column, I had a rule about having no more than two unfinished Vollmanns on my shelf. With this one down, I have one more remaining. It’s at least a few months out but we can all look forward to me tackling his most popular book, the surprise winner of the 2005 National Book Award, Europe Central. What this also means is that maybe I can go back to Lot 49 and get that waterlogged copy of Rising Up and Rising Down.